Frederick Matthias Alexander

Frederick Matthias Alexander (1869–1955) was a Shakespearean orator who developed voice loss during his unamplified performances. After doctors found no physical cause, Alexander reasoned that he was inadvertently damaging himself while speaking. Alexander’s promising career as a young actor was threatened by recurring vocal problems. He sought the help of doctors, but to no avail. Since there was no clear medical cause for his problem, Alexander thought he might be doing something wrong when reciting, leading him to strain or ”misuse” his vocal organs.

He observed himself in mirrors and noticed that he stiffened his neck, pulled his head back and down and depressed his larynx. This went with an audible gasping for air as he opened his mouth to speak. This seemed to be the root of his problem.

It gradually became clear to him that this was part of a bigger pattern of tension involving the whole of his body. This tension pattern manifested itself at the mere thought of reciting.

Alexander spent several years working out a way to change this habitual reaction and learn how to prevent this harmful misuse pattern, thereby improving his health and functioning in general.

As he improved his vocal use, breathing and stage presence, other people started coming to him for help. From about 1894 onward, he started teaching his discoveries in Melbourne, and later in Sydney, until teaching became his main occupation.

A number of doctors referred patients to him. In 1904 he brought his Technique to London, with letters of recommendation from JW Steward MacKay, an eminent surgeon in Sidney.

He established a thriving practice in London, published four books (link to books) and from the 1930s trained about 80 teachers in his Technique. He never returned to his native Tasmania and continued to teach right up to his death in London in 1955.

It gradually became clear to him that this was part of a bigger pattern of tension involving the whole of his body. This tension pattern manifested itself at the mere thought of reciting.

Alexander spent several years working out a way to change this habitual reaction and learn how to prevent this harmful misuse pattern, thereby improving his health and functioning in general.

As he improved his vocal use, breathing and stage presence, other people started coming to him for help. From about 1894 onward, he started teaching his discoveries in Melbourne, and later in Sydney, until teaching became his main occupation.

A number of doctors referred patients to him. In 1904 he brought his Technique to London, with letters of recommendation from JW Steward MacKay, an eminent surgeon in Sidney.

He established a thriving practice in London, published four books (link to books) and from the 1930s trained about 80 teachers in his Technique. He never returned to his native Tasmania and continued to teach right up to his death in London in 1955.

Recognition

In London, Alexander's reputation grew rapidly. Eminent students of his include George Bernard Shaw, Aldous Huxley and Lillie Langtry.

A number of scientists endorsed his method, recognising that Alexander’s practical observations were consistent with scientific discoveries in neurology and physiology. The most eminent of these was Sir Charles Sherrington, today considered the father of modern neurology.

Another Nobel Laureate, Nikolaas Tinbergen, who won the prize for “physiology or medicine” in 1973, dedicated a significant part of his Nobel acceptance lecture to the work of Alexander. You can watch his speech here.

Many doctors, including Peter MacDonald, who later became chairman of the BMA, were advocates of his work and sent patients to him. In 1939, a large group of physicians wrote to the British Medical Journal urging that Alexander’s principles be included in medical training.

With its wide application, Alexander’s technique drew people from all walks of life, including politics (Sir Stafford Cripps and Lord Lytton), religion (William Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury), education (Esther Lawrence, principal of the Froebel Educational Institute) and business (Joseph Rowntree).

A number of scientists endorsed his method, recognising that Alexander’s practical observations were consistent with scientific discoveries in neurology and physiology. The most eminent of these was Sir Charles Sherrington, today considered the father of modern neurology.

Another Nobel Laureate, Nikolaas Tinbergen, who won the prize for “physiology or medicine” in 1973, dedicated a significant part of his Nobel acceptance lecture to the work of Alexander. You can watch his speech here.

Many doctors, including Peter MacDonald, who later became chairman of the BMA, were advocates of his work and sent patients to him. In 1939, a large group of physicians wrote to the British Medical Journal urging that Alexander’s principles be included in medical training.

With its wide application, Alexander’s technique drew people from all walks of life, including politics (Sir Stafford Cripps and Lord Lytton), religion (William Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury), education (Esther Lawrence, principal of the Froebel Educational Institute) and business (Joseph Rowntree).

Alexander Technique and Education

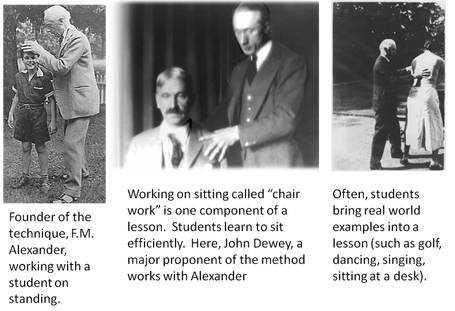

Alexander spent some time in the USA, where he met and gave lessons to philosopher John Dewey, the “father of the American education system”.

Dewey asserted that effective learning must be based on first-hand experience; he demonstrated his support and enthusiasm for Alexander's work by writing the prefaces to three of Alexander’s books.

Alexander believed it was important to incorporate his technique into the education of children. In 1924 he founded the ”Little School”, helped by two of his assistants, Ethel Webb and Irene Tasker, who had also been trained by Maria Montessori in Italy. In the school, children were encouraged to apply the Alexander principles during lessons and in all other activities. The children were evacuated to the USA during the Second World War and the school was never re-established.

AmSAT is the American Society for the Alexander Technique is the largest professional association of certified Alexander Technique teachers in the United States.

Dewey asserted that effective learning must be based on first-hand experience; he demonstrated his support and enthusiasm for Alexander's work by writing the prefaces to three of Alexander’s books.

Alexander believed it was important to incorporate his technique into the education of children. In 1924 he founded the ”Little School”, helped by two of his assistants, Ethel Webb and Irene Tasker, who had also been trained by Maria Montessori in Italy. In the school, children were encouraged to apply the Alexander principles during lessons and in all other activities. The children were evacuated to the USA during the Second World War and the school was never re-established.

AmSAT is the American Society for the Alexander Technique is the largest professional association of certified Alexander Technique teachers in the United States.

What does "AmSAT-certified" mean?

The requirements for AmSAT teacher certification are specified in AmSAT's Bylaws and include the completion of 1,600 hours of training over a minimum of three years at an AmSAT-approved Teacher Training Course. AmSAT Teacher Training Courses maintain a five-to-one student/teacher ratio. The AmSAT Teacher Certification Requirements can be found here . More information about AmSAT teacher training programs can be found here.

To receive Board approval, an AmSAT Teacher Training Course must meet the requirements of the Training Approval Committee (TAC). The TAC periodically reevaluates each of AmSAT's teacher training programs and their directors.

To receive Board approval, an AmSAT Teacher Training Course must meet the requirements of the Training Approval Committee (TAC). The TAC periodically reevaluates each of AmSAT's teacher training programs and their directors.